Compounded Effects of Multi-Layer Academic Tracking Disadvantages Black and Hispanic Students

By Ronit Morris

In New York City, your race determines where you go to school. This is sadly no surprise.

Academic tracking, the sorting of students onto different educational paths, takes place on two levels: tracking between schools and tracking within schools. This double tracking advantages White and Asian students while disadvantaging Black and Hispanic students.

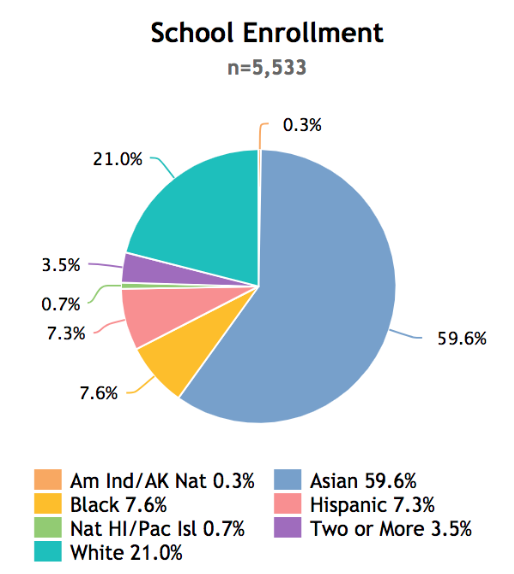

Tracking between schools functions as a racialized sorting of White and Asian students into higher achieving and better resourced schools than Black and Hispanic students. This sorting can be seen in the racial makeups of students at two Brooklyn schools: Brooklyn Technical High School and Victory Collegiate High School. In 2015, Brooklyn Tech was 59.6% Asian, 21% White and only 7.6% Black and 7.3% Hispanic. By contrast, Victory Collegiate was: 87.6% Black and 6.5% Hispanic and only 1.2% White and 0% Asian.

Figure 1: School enrollment by race at

Brooklyn Tech.

Figure 2: School enrollment by race at Victory Collegiate.

These numbers reflect a typical pattern of racialized sorting, with White and Asian students concentrated in some schools and Black and Hispanic students concentrated at other schools.

Students are admitted to Brooklyn Tech using the Specialized High School Admissions Test, the theoretically race-blind test that determines which students get offered a spot at seven competitive high schools. The demographic makeup of Brooklyn Tech reveals that, in practice, the test functions to sort students by race.

Asian and White students were both more likely to take the test than Black of Hispanic students, and they were also more likely to score higher. In 2019, nearly ⅓ of the students who took the test were Asian and over 18% of them were White, “percentages that are higher than the citywide public school enrollment for both groups.” Not only were White and Asian students more likely to take the exam, they were more likely to do well: only 5% of Black or Hispanic testers were offered spots, while almost 30% of the White and Asian students received offers.

This year, Brooklyn Tech admitted 884 Asian and 573 White students, but only 117 Latino and 95 Black students. These admission stats are after the widening of the Discovery program, Mayor De Blasio’s administration’s attempt at desegregating the Specialized schools. The program reserves a few spots at the Specialized schools for Black students who did not make the test score cutoff.

The 2019 admissions numbers show this to be an insufficiently effective initiative to increase these populations in these schools. The Discovery Program was created to increase the number of Black and Latinx students in the Specialized schools, but yet these students are still vastly underrepresented: This year only 7 black students were offered spots at Stuyvesant High School, another specialized school that uses the same test at Brooklyn Tech, and which has even fewer black students. Despite this attempt at desegregating these schools, the test continues to be a tool for tracking Black and Hispanic students out of the most competitive schools.

Black and Hispanic students experience the compounded negative effects of tracking between schools and tracking within schools. One measure of this tracking is the set of courses that students are offered within the schools that they get tracked into. Predominantly Black schools usually offer fewer classes than those with more white students, and the classes they do offer are typically at a lower level. Specifically, they often offer fewer Advanced Placement (AP) or similar college-ready courses. Using the same comparison between Brooklyn Tech and Victory Collegiate, the pattern becomes concrete: Brooklyn Tech offers five standard levels of mathematics (Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II, Advanced Mathematics, Calculus) and three standard levels of science (Biology, Chemistry and Physics – No Algebra II or Calculus). Brooklyn Tech also offers 20 different AP courses and enrollment in these classes is the norm: 57% of students are enrolled in at least one.

Victory Collegiate, on the other hand, offers only only three standard levels of math (Algebra I, Geometry, Advanced mathematics – no Algebra II or Calculus) and only one standard science class (Biology). Victory Collegiate only offers 2 AP classes and enrollment in these classes is definitely not the norm: only 7% of students are enrolled in at least one AP course.

Another way that tracking within school manifests is in the numbers of students who take the SAT or ACT. 32% of students at Brooklyn Tech took the SAT or ACT in 2015, but only 13% of students at Victory Collegiate took either test that year.

The Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (OCR) lists SAT or ACT registration, along with enrollment in Chemistry, Physics and Calculus, as one of the indicators for “college and career readiness” of students. According to these measurements, the students at Victory Collegiate are significantly less prepared for college and careers than their peers at Brooklyn Tech. Their high school did not provide the necessary courses for them to be competitive candidates for college, nor did it encourage most of them to take the exams necessary to apply. In a world where a Bachelor’s degree is increasingly important in the job market, this will make them less competitive candidates for jobs. Students who do not go to college will likely make less money than those students who do go to college, and because most of these students are Black and Hispanic, this will further widen the racial income and opportunity gap.

Because of the sorting of students into high schools along racial lines and the offering of better educational opportunities in mostly White and Asian schools than in Black and Hispanic ones, Black and Hispanic students are put at an educational disadvantage that will affect their life and economic outcomes as adults, furthering the racialized socioeconomic gap in our society today.

In order to break this cycle, there would need to be interventions on both levels of tracking. Black and Hispanic students need to be admitted to selective high schools in proportionate numbers to their White and Asian peers, and all high schools need to offer courses and provide materials that prepare students for college. As all of this requires funding, the burden ultimately falls on the government to fund schools that are predominantly Black the same way it funds schools that are predominantly White.