The School Renewal Program is ineffective and unfair. Mayor of New York Bill de Blasio recently (January 2019) admitted that his School Renewal Program intended to fix New York City schools was a failure, costing city taxpayers $773 million and leaving mostly Black students with more limited school options. The program, which sought to improve 94 schools and has closed 14 and merged 9 other schools, was vastly racialized. Because of the way the program ranked, schools that hold families that are mostly low income were put under the program. In addition, the students with the most privilege ended up benefiting, and schools that needed improvement ended up not only suffering but, even closing.

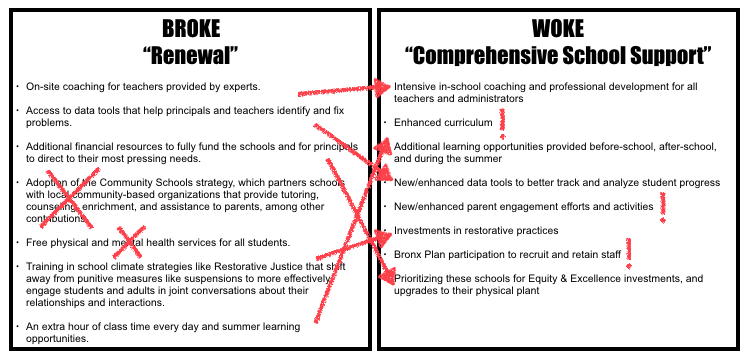

Richard Carranza, the school’s Chancellor of NYC says there is “no clear theory of action.” We cannot celebrate that De Blasio finally ended the ineffective and destructive School Renewal Program until we replace it with a system that is more effective. De Blasio’s program was harmful in its effects but well intended. The policy of closing schools that were failing began with Bloomberg after he was given control of the system in 2002. De Blasio, when he took office, announced that an extra $150 million would be put into improving 94 of the city’s lowest-performing schools that year. However, tax payers were paying for improvements that did little to nothing, and caused people who could leave “failing” schools behind to do so. Going forward, a new system must implement initiatives that will give students the support the program intended. Such initiatives should include a new grading system to distinguish schools that need support, supportive language for schools who need it, community control over funding, and stable student support through an advising system.

Under the School Renewal Program, evaluative systems valued schools where students had higher test scores and grade point averages, which are often dependent on what access the students have to outside resources. Determining the failure or the success of a school on test scores is an inherently racialized act since white kids have disproportionate access to outside tutoring. If you refer to the map page, you can see that the schools under the renewal program are mostly in neighborhoods with low-income families. In fact, it is well-established that test scores do not reflect a person’s academic or intellectual ability. As such, this paradigm is not only misrepresentative, it is also racialized: Children of white families who have high income (itself a related phenomenon) also usually have access to tutors, time with their parents (who are most likely educated themselves), and good health. These factors are intrinsically intertwined with higher grades and test scores. Not to mention, privileging schools based solely on quantitative data is unfair to English learners.

Due to the abandoned School Renewal Program, now is the time in which we can build a new system and grade schools on a holistic basis. De Blasio mentioned a solution, a new data system called EduStat, which is meant to give officials a more authentic sense of school performance. While it can be useful to use grades and test scores, a new system should also factor a myriad of skills such in science tests, career readiness, rates of chronic absenteeism and progress among English learners, not just state exams. Systems must also give credit to schools that improve, whether or not they meet an average state score. A comprehensive grading classification will allow all students to be awarded for their specific talent and will help deconstruct the idea that one skill is more valued than another. All students should have the opportunity to be high achieving, not just white students who have access to extra support.

The Renewal Program also failed because of the way that schools under the Renewal Program were labeled: it lead white, high-income students to leave due to their fear of attending a school with a bad reputation and one that was slated or likely to close. In order to minimize drawing a parallel between underperforming schools and failure (and closing), we must designate schools in a way that is similar to the “Comprehensive Support and Improvement Schools” designation, which is language formed by state educational agencies that label schools as supportive and comprehensive. A study revealed that student enrollment falls by at least 16% when the school is labeled “failing” and put under the School Renewal Program. This creates a paradox because often school funding is dependent on the number of students that attend the school. If a school is underfunded, it is more likely to be underperforming, and thus labeled as “failing” instead of “improving.”

Once a school is labeled with terminology that is hopeful and promises support, these labels should not have high stakes. This way more schools could be labeled and thus receive the support they need without facing any consequences. Under this supportive label, the state will not require leadership changes or make teachers reapply for their jobs.

In order to effectively support and improve schools as our new label suggests, New York City should offer to fund for support programs and services. Some examples are academic support, before and after school tutoring counseling, mentoring, supplemental supplies for homeless students, and parent and family engagement workshops. Even if the School Renewal Program did implement some of these initiatives, in a new system’s future plans, these must be included and implemented. Most importantly, schools should be held accountable for the ways in which their school is falling behind: Perhaps by giving the school community a fund of at least $2,000 and letting them vote on how it can be used best. This system would have to be regulated properly and there need to be active orders in place to minimize the risk of designating some votes more powerful. Centering community voices is the most effective and efficient way of attending to their needs.

It is especially important for schools to use funds for an advising system. This would be an alternative to “looping,” which also has good intentions, but is risky in practice. Looping is when a teacher stays with a cohort of students for more than one year. Its benefits are that it creates stability for students who may not have it at home and provides a consistent role model in their lives. Looping, though, should be dependent on the teacher and their preference. When teachers loop, they must create a new course plan for their class every year. This would be an extreme amount of labor that teachers would surely not be compensated for, as most educators are already underpaid. Having supporters and advisors is an efficient way of encouraging students and giving them necessary access to improving such as advice about how to develop a student-teacher relationship, or encouragement to start thinking about passions, and advisors can also excuse students from classes without penalty if it is necessary for someone who needs the time off.

A great opportunity presents itself when bad things fail. In order to use this chance effectively and not see it also fail, the utmost important policy and practice we must change is the diversity of leadership. To put a Black leader or teacher in charge of a school or a system that grades the quality of the school would be implementing a voice into leadership that is from a community that is most vulnerable to school closing In the wake of De Blasio’s failure and the potential to have better schools for all children, we must keep progressing and we must keep centering Black voices and needs.

By Adrian Silk