by Ansley Carlisle

For students across New York City, the spring 2019 semester saw a wave of protests in support of school discipline reform. From students leading protests against racism in school disciplinary practices in the Bronx to families protesting lengthy suspensions in schools at City Hall, New Yorkers across the city are raising concern about current disciplinary practices. Yet a recent New York Post op-ed by NY Democratic State Sen. Leroy Comrie stood in stark contrast against the students’ messages. In an emphatic call-to-action for reform of New York City’s school discipline policy, Comrie criticized recent school discipline reform as a contributing factor of unsafe school environments. Interestingly, beyond citing stories from two teachers assaulted by students to support his stance, Comrie provided no other concrete examples or research to bolster his claims.

The discourse that supports strict enforcement of school discipline–especially exclusionary discipline–tends to use specific incidents of student violence to paint a generalized picture of rampant disorderly conduct in schools without strict disciplinary practices. This is ever-apparent with Comrie’s discussion of two student assaults requiring “medical attention…for the assaulted educators.” These arguments usually evade the fact that most suspensions are given out for non-violent and subjectively-determined “disruptive” behavior and not physical altercations with teachers as Sen. Comrie might suggest.

Data reveal an interesting phenomenon with regard to the causes and the lengths of suspensions. According to a 2018 study, black students in New York City schools tended to receive longer suspensions for 80% of the most common infractions that researchers studied. In the infraction category of reckless behavior–which is differentiated from group violence–black students received–on average–suspensions that were 9.4 days longer than those of their white peers.

Since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office, suspensions have decreased by 32% overall. This decrease was due in large part to de Blasio’s support of policies aimed at limiting the number of suspensions, such as a discipline code that adds another approval step before issuing suspensions for certain violations. While the number of suspensions in NYC schools has decreased under Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration, the racial distribution across infractions has not changed. This research points to the ineffectiveness of the city’s school discipline reduction efforts in addressing the racism within exclusionary discipline practices.

The conversation around effective modes of school disciplinary practices is important. However, equally important in school discipline reform discourse is addressing how to decrease racial discrimination within any disciplinary procedure. Research out of the Kirwan Institute exploring the connection between implicit racial bias and disparities within school discipline reveals the importance of addressing school discipline reform through the specific lens of racial bias. Researcher Cheryl Staats asserts that “many of the infractions for which students are disciplined have a subjective component, meaning that the school employees’ interpretation of the situation plays a role in judging whether (and to what extent) discipline is merited.” Thus, it is important to hold school teachers and administrators accountable for their racial biases as these directly impact student disciplinary outcomes.

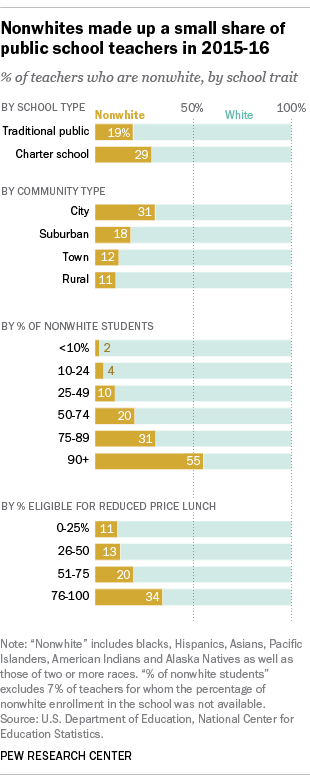

According to a report by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics, approximately 80% of America’s public school teachers are white; 9% of teachers are Hispanic and 7% of teachers are black. These statistics stand in stark contrast to the ever-diversifying population of students in public schools. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows that 51% of public school students are of color. Considering the pervasive, negative perceptions of black and brown people in this country, one can easily imagine that racial stereotypes held by some white teachers can have a significant impact on disciplinary practices used against perceived deviant behaviors. As Staats affirms, “pervasive societal implicit associations surrounding Blackness (e.g., being dangerous, criminal, or aggressive) can impact perceptions of Black students in ways that affect the discipline they receive.”

New York City has begun to make strides toward anti-bias training for public school teachers and administrators. The more that these efforts are linked to the work of school discipline reform, the school discipline reform discourse will more equally weight the importance of bias with the importance of disciplinary practices as they relate to racial disparities in school discipline. This is important because, ultimately, it will help change the public perception of the behavior of students of color in schools. Ideally, as the public understands the contribution of racial stereotypes to racial disparities in school discipline, racism–and not errant behavior–will be centered in the school discipline reform discourse.

That Mayor de Blasio’s efforts to address school discipline fall short of reducing racial disparities in discipline statistics calls into question the nature of the city’s racial bias training program. Does it inform white teachers of the inextricable linkage between their biases and their disciplinary practices? Are these teachers given the tools to actively practice arresting their own judgements about students before handing out suspensions?

Staats suggests that it’s not enough for a teacher to only acknowledge that he has racial biases: “While an important first step, mere awareness of implicit bias is “not sufficient to reduce the automatic, habitual activation of stereotypes and the subsequent impact of implicit bias”.”

She argues that teachers must do more than become aware of their internalized stereotypes of students of color by working to debunk the biases. To this point, Staats cites research which suggests the effectiveness of teachers connecting with their students’ cultural norms and practices in order to reduce instances of misunderstanding–on behalf of the teacher–that result in needless disciplinary action. This practice can manifest in what researchers at Brown University’s Education Alliance call “culturally responsive teaching”. According to this group, culturally responsive teaching incorporates students’ cultural backgrounds into their learning environment through communicating high expectations, facilitating student-centered instruction, and maintaining positive perspectives on students’ families among other practices. According to the alliance, this work “offers full, equitable access to education for students from all cultures.”

The conversation about the length and frequency of suspensions is not productive in a vacuum. Until schools work to mitigate the subjective bias that results in racial disparities within suspension practices, black students will continue to suffer from unjust disciplinary practices of any form. Mayor de Blasio’s efforts toward racial bias training for school employees is a good first step. However, considering the continued racial disparities within school discipline, perhaps it’s time to consider rethinking how effectively school teachers and administrators are trained to actively identify and restrain their own biases especially as they consider meting out suspensions.