The Proposal to Eliminate the SHSAT is Not Enough

By Carmen Cheung

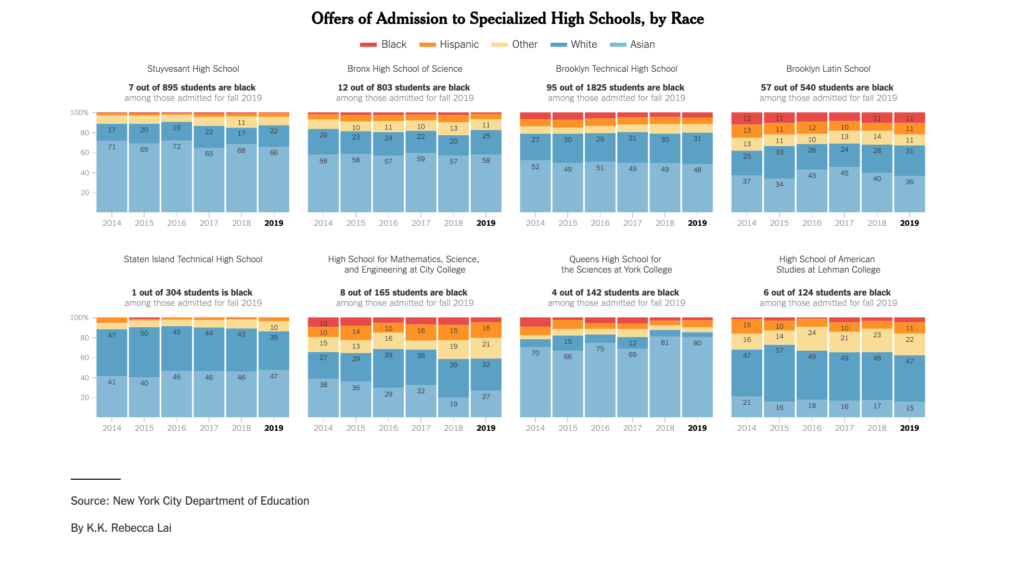

There’s a problem when it isn’t surprising to hear that only seven out of the 895 admitted students to Stuyvesant High School were black this year.

There’s a bigger problem when the city’s solution is superficial in addressing the racial inequality at the specialized high schools, as racial inequality is rooted the entire New York City public school system.

Last June, Mayor Bill de Blasio and Chancellor Richard Carranza announced their solution to this ongoing problem of racial homogeneity in Stuyvesant and the seven other specialized schools like it: Eliminate the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test (“SHSAT”), the exam eighth grade students must take and score high enough on to be offered a spot.

For de Blasio and Carranza, the accessibility to preparation for this test is what produces the racial disparities in student population favoring White and Asian students. de Blasio explicitly writes, “Why should some families who can ill afford test prep have to spend their money on it? Why should some families who can easily afford test prep have an advantage over those who cannot?”

For them, eliminating the SHSAT would eliminate the preparation needed for it. Their overall goal is to implement a more holistic admissions process that takes students’ statewide test results and in-class grades into consideration. By offering spots to eighth graders who are both in the top 7% in their public middle school and the top 25% of all public school students in the city, the proposal hopes to create “Equity and Excellence for all.”

In simulating the effect of taking the top 10% of eighth graders in every public middle school similar to the proposal, a study at New York University finds that this is the only way to guarantee an increase in Black and Latinx students in the specialized high schools. However, it discovers that a policy comparing public school students citywide on the same measures of achievement along with attendance would actually harm Black students’ chances of being admitted into specialized high schools.

What this indicates is that the racial inequality in access to learning doesn’t begin at preparation for the SHSAT – it begins in elementary and middle schools.

By focusing on the test prep that tends to advantage White and Asian students, de Blasio and Carranza effectively ignore that Black students already learn less relative to their White and Asian peers during their formative years before high school. The study at NYU reveals that Black students’ are less prepared for high school given their inability to compete with their peers citywide on the basis of their statewide test scores and in-class grades. With that, the racialized results of the SHSAT are only indicative of this racial disparity in learning experiences ridden in the city’s entire public school system.

Historical analysis of the demographic change in specialized high schools suggests that the homogeneity problem is larger than the admissions process. Although racial and ethnic makeups at the specialized high schools were never perfectly reflective of citywide student demographics, there was a time when they served more Black and Latinx students. Right before New York City cut all of its middle school honors programs in the nineties following the trend of other school districts across the nation, Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, and Brooklyn Tech respectively had 10%, 22%, and 51% of their students identify as Black or Latinx, which is much more than recent trends.

Before the nineties, even though middle schools were noticeably segregated, there were still honors programs at predominantly Black and Latinx schools where Black and Latinx students were valued by their teachers for their academic endeavors. Two Afro-American experts find that students can tell whether or not their teachers are invested in them. Interviews with Black students elucidated they were aware that their race made them vulnerable to lesser expectations from their teachers, affecting how they were taught.

Honors classes in middle schools were spaces where Black and Latinx students were offered education more comparable to their White and Asian peers at other schools because their teachers saw potential in their ability to learn and grow. Without educators who recognize that Black and Latinx students are just as capable as White and Asian students, Black and Latinx students don’t feel safe or motivated to be academically curious.

In order to truly redress the consistent lack of diversity in the specialized high schools, de Blasio and Carranza must give greater attention to fostering environments that support learning for all Black and Latinx students by retraining educators to see value in their disadvantaged students so that students themselves are motivated.

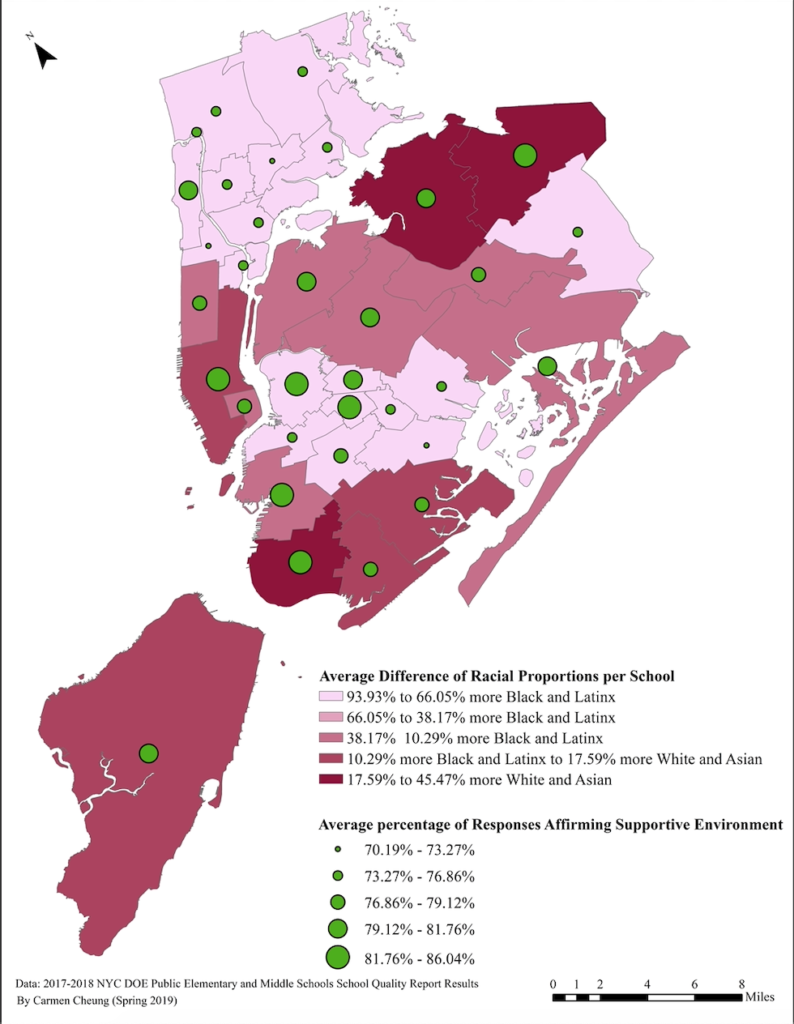

Recent data collected by the city’s Department of Education reveal that there is, indeed, a difference in perceived support where there are differences in racial and ethnic composition in the student body. In districts where elementary and middle schools have proportionally more Black and Latinx students than White and Asian students per school, the environment is said to be less conducive to learning.

Data source: 2017-2018 NYC DOE Public Elementary and Middle School Quality Report Results

Research suggests that this difference may be attributed to the majoritarian narrative that educators have been subconsciously led to believe. This widely held narrative based on the crass stereotype that Black students don’t perform well in schools because of a lack of achievement-promoting culture in their homes diverts the blame from systemic sources of racism to more individual, unchangeable characteristics of a student. Such a diversion compels educators to believe that Black students are just unwilling to learn. There is no motivation for teachers to create classrooms catering to their disadvantaged students.

With that, it’s vital to promote counternarratives in both mandatory public school teacher training and student curricula. Before entering classrooms, educators should be made aware of their internal biases set by the majoritarian narrative and retaught to consider the other factors hindering their Black and Latinx students. This shift in perspective will help educators realize that disadvantaged students can be inspired to learn if they know their teachers believe in them. Such a realization will motivate teachers to come up with new ways to meet their students’ needs. This new methodology focuses on potential. Thus, Black and Latinx students who may not place in the highest ranks at the start of the year can be valued for their growth over time. Furthermore, by incorporating the creation of counternarratives into curricula for students, teachers will develop stronger relationships with their students as they help them construct their individual stories.

While it’s important that de Blasio and Carranza want to diversify the city’s best schools, they disregard the learning disparities across more schools that affect who gets into the specialized high schools. To truly attain equity and excellence for all, we must push them to take on the challenge of addressing the racial disparities in the entire public school system.

Carmen Cheung is in the Dual Program between Columbia University and Sciences Po Class of 2020 in the School of General Studies. She grew up in New York City and graduated from the Bronx High School of Science Class of 2016. In being wanting to learn about the inequality in the city, she is majoring in urban studies and concentrating in statistics.